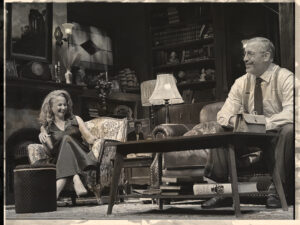

photo by andrée lanthier

One of my favourite things about the production of Wendy Lill’s play The Glace Bay Miners’ Museum, now playing at Neptune Theatre’s Fountain Hall, is that it is a Co-Production with the National Arts Centre in Ottawa, where the show ran earlier this season, and yet, it has a distinctly Nova Scotian cast and creative team. This is far rarer than it should be for Neptune, where Co-Productions don’t often give the opportunity for Nova Scotian-based actors to perform in other cities or to be the central characters in the story. The theatre is such an integral medium for telling the stories of home, our stories from our communities, and it is vital that Neptune Theatre, as Halifax’s regional theatre, continues to show its commitment to fostering a theatrical experience that enriches and reflects who we are as Nova Scotians.

The Glace Bay Miners’ Museum is based on a short story of the same name written by Sheldon Currie in 1979 and adapted for film (1995’s Margaret’s Museum starring Helena Bonham Carter). Lill’s play was first produced in 1995 for Ship’s Company and Eastern Front Theatre here in Nova Scotia. It has been argued that because the play is not new and that it captures vividly life in Cape Breton in the 1940s, it has become a sort of museum piece unto itself. Yet, I think that the fundamental questions Currie and Lill raise here: “What price do we pay for fighting to honour our heritage, to preserve our past, our history and our culture?” and “What price do we pay to fight for what is right, what is fair and what is just for the people?” could not be more relevant in the time of the Idle No More and Occupy Movements that have been sweeping the globe.

The story centers on Margaret MacNeil, a young girl with the dubious reputation of being a “snot nosed whore,” who lives in a small shack in Reserve Mines, Nova Scotia and whose family is still mourning the loss of her father and beloved older brother in a mining accident. The story unfolds as a retrospective told from Margaret’s point of view and she is later revealed to be an unreliable narrator, which accounts for the scenes having an inconsistent or even slight Expressionistic quality about them. Sometimes the characters and situations seem so big, broad and stereotypical that it seems like Lill is creating a pastiche of rustic Cape Breton. Yet, this is contrasted continually with beautiful intimate scenes that allow the characters’ intricate dynamics with one another to come alive, and allow the actors to honour the complex idiosyncrasies that make these five people specific individuals rather than representations of “types of people one might encounter in a small Cape Breton mining town.”

The result is that there is so much to love in this play, so much earnest emotion, captivating storytelling, the clashing of ideals that never feel too didactic or “concept heavy” and it makes for ardent and riveting kitchen sink realism. The challenge is that Lill’s play isn’t constructed to be entirely realistic and the arc of the play crams much of the real climatic, emotional action into the very last section of the play and has it narrated rather than unfolding dramatically as the expositional scenes do. This is jarring for the audience because the play stylistically careens off into unfamiliar territory and, while this does mirror Margaret’s journey, the audience is not given the chance to delve deep enough into Margaret’s personal anguish and psyche to justify alienating them from their investment in the other characters at the very end of the play.

Director Mary Vingoe roots the piece in a very familiar theatrical realistic style, with the set serving the purpose for multiple locations, but doesn’t go as far as to suggest Lill’s Expressionistic undertones. This works beautifully for much of the play, but becomes problematic as it cannot contain the play’s ending in a way that is truly satisfying. I would be interested to see this play done in an overt Expressionistic style, as perhaps it would root the audience more firmly in Margaret’s world and make it more clear that there is more to the story she is telling than initially meets the eye.

The actors make it impossible not to fall immediately under their spell and to want to connect ardently to each character’s tragic and wide open heart. Francine Deschepper is charming, sweet and lovely as Margaret, an immediately likeable ingénue with just enough pluck and feistiness to keep her story perpetually interesting. I thought Margaret could have had an even harder outer shell at times and been a little bit edgier and darker given the tragic and difficult circumstances of her life, but Deschepper is so irresistible and joyous to watch, I willing suspended my disbelief. She falls in love with Neil Currie, played by Gil Garratt, an uproarious idealist and bagpiper who longs to return to the simpler ways of his ancestors, but finds himself caught in a trap of unemployment, disillusionment and drunkenness. Deschepper and Garratt have beautiful chemistry together and an endearing playfulness that makes you want to see them succeed, despite Currie’s flaws. Jeff Schwager also develops a great chemistry with Garrat as Margaret’s brother Ian, a fastidious and practical Union man who dreams of reforming the mines that killed his father and brother. Martha Irving is a pillar of strength as Catherine, the world-worn matriarch whose resourcefulness and brutal prudence is what keeps the family with a meager meal in their bellies and an (albeit leaking) roof over their heads. David Francis, in the non-speaking role of Grandpa, is the beating heart of the play. He is a revelation in how much depth of emotion, character and wisdom can be conveyed with facial expressions and gestures and the intermittent joyous lighting up of his face, as though his soul had suddenly caught fire.

What is most interesting for me about the themes Currie and Lill are exploring in The Glace Bay Miners’ Museum is the idea of the loss of our cultural identity, a quiet assimilation, and a disconnect between what we must do to survive and to succeed here versus the values of our ancestors. I consider myself to be an English-speaking Nova Scotian because English is my first language. Yet, upon reflection, I realize that most of my ancestors did not speak English when they first arrived on these shores; some of them spoke Gaelic and some of them spoke French. Since the time this play is set, Cape Breton Island has invested ardently in preserving its Scottish heritage and, therefore, has a very vibrant, tangible culture and sense of its own history. This is beautiful and enviable and makes me wonder where that leaves the rest of the Province. Nova Scotia is becoming increasingly multicultural and we see our Lebanese, Greek and Indian communities (just to name a very few) celebrating their cultures and being a beautifully visible part of the mosaic of Nova Scotia, perhaps we, whose ancestors arrived here hundreds of years ago, should be taking a bit of Neil Currie to heart and making sure that we are, figuratively, reading the scribblers of our past instead of just using them for fly swatters.

The Glace Bay Miners’ Museum plays at Neptune Theatre’s Fountain Hall (1593 Argyle Street) until March 17th. Show Times are: Tuesday to Friday at 7:30pm. Saturdays at 4:00pm and 8:30 and Sundays at 2:00pm and 7:30pm. Tickets from $20.00 to $41.00. Tickets can be purchased by calling 902.429.7070 or in person at the Box Office at 1593 Argyle Street or online. For more information please visit this website.