After seeing boo at the Atlantic Fringe Festival, written and performed by Charlie Rhindress and directed by Daniel MacIvor, I was struck by the fact that this was the first time I had seen MacIvor direct someone else’s work. Indeed, here it seemed like Rhindress was in the traditional MacIvor role and MacIvor was in the role typically played by Daniel Brooks. So, I wanted to sit down with Daniel and chat about boo and this process and his upcoming projects, but since he is currently in Sydney, Cape Breton and I’m currently in Halifax, we both had to sit down at our computers, and through the magic of email, I’m happy to bring this interview to you:

Amanda Campbell (AC): How did you and Charlie Rhindress first meet and how did you become involved in the development of boo? You seem to compliment each other nicely, especially artistically, was that immediately apparent?

Daniel MacIvor (DM): I first met Charlie when he was performing in a nine hour experimental “Hamlet” produced by DNA theatre in Toronto in the early 90’s. Oddly, when the play transferred to Montreal and Charlie couldn’t go, I took over his part. It was Guildenstern. A small part normally but huge when the play is nine hours long. I became involved in “boo” when Emmy Alcorn, from Mulgrave Road Theatre, and I were talking about his “Harry Delany” postings on Facebook. I mentioned to Emmy that I thought there might be a show in the material and said I’d be happy to help out. I didn’t realize at the time that “helping out” meant directing, but that’s how Mulgrave Road works. It was clear from the outset that Charlie and I would work well together because he didn’t argue with me for the sake of “being right” and he was happy to let me be a tough bastard when necessary. He doesn’t take things personally, a rare gift in an actor.

AC: Often you can be seen directing your own work (as in the case with How It Works, You are Here and Marion Bridge) or you and Daniel Brooks collaborate on your solo pieces like Monster and Cul-De-Sac. How is the process different when you are working on a piece that you didn’t write?

DM: When directing other people’s plays it works best when I am also the dramaturge. I can get my hands dirty and I feel invested in the writing. It’s similar to how Brooks and I work on the solos.

AC: Charlie mentioned to me that boo is very different from his original conception of the show, and that you were instrumental in drawing the heart of the story out of him as a performer. Can you talk a little bit about how that evolution process came to be? Are there any of your plays that ended up being completely different from your initial concept?

DM: Many of my plays end up being completely different than the initial concept. Just ask Emmy Alcorn, or Daniel Brooks, or Iris Turcott, or anyone else I’ve worked with. In terms of the evolution of boo, I’ve been working on an idea called Play Finding. I tried it out in a one day Masterclass at Natasha Mytnowych’s development festival at Canadian Stage in the Spring, and I’ll be doing a weekend version at Banff in December. Basically it’s looking at a writer’s work and drawing out the self from the work, seeing how the heart of the work is connected to the heart of the writer, finding the truth of the play by connecting it to the truth of the writer. This was very much how I worked with Charlie.

AC: When you’re dealing with a play that centers on the very personal experiences of the performer involved, as a director do you approach this differently than you would a play that has more semblance of fiction?

DM: I’m really only interested in work that is based on “personal experience” somehow. I think it can be argued that most plays are, certainly the best plays are. There are those that will say Howard Barker isn’t working from “personal experience,” but he is working from a “personal” philosophy based on his “personal” experience. Of course superficially or semantically, Charlie’s play is more “personal” than most. I’m also working with Linda Griffiths on her play “Last Dog of War” as her director/dramaturge, this is also a very “personal” play. Even moreso than Charlie’s in that in the play Linda’s character’s name is “Linda” and she describes in detail a trip she took with her father. In this kind of process the approach is probably more dramaturgical than directorial.

AC: Your programme bio states that you live in Halifax and Toronto. A year and a half ago I heard you speak in Toronto and you said that you wanted to return to Halifax but that it was too difficult for a professional playwright to survive there. Has that changed at all in the last year and a half? Is there anything specific that you see in need of development so that Halifax can continue to foster its indigenous playwrights?

DM: I have become involved in a new theatre company founded by Kathryn MacLellan, Jackie Torrens and myself called DTS (Distinct Theatre Society), which is based in Halifax. So my connection to Halifax is more as a producer right now than as a playwright. Toronto is my playwright home. I think in order for Halifax to become a community that develops and nurtures playwrights, people who control theatre in that city have to make the development and nurturing of playwrights a priority. The regional theatre must start some kind of Playwrights Unit or Playwrights Colony or Playwrights Tea Party or whatever they want to call it, where playwrights meet weekly and bring in new work to be discussed and developed with the aid of dramaturges, directors, actors and designers. Playwrights are craftspeople not vegetables, they don’t grow like cabbage or rhubarb, they are mentored and trained like blacksmiths or architects. It can’t happen in a vacuum. Or in a mound of manure.

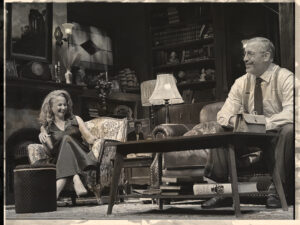

AC: Can you speak a bit about your new play Confession?

DM: “Confession” is the first play in a trilogy – the second two being “Communion” and “Redemption”. All three plays are for three women and all deal with a search for meaning. In the case of “Confession” it is the most poetic of the three and deals with a woman at the end of her life, the decisions she’s made, the responsibility she’s avoiding and the truth she’s afraid to tell. (Wow, that sounds like a press release.) And speaking of press release, it’s directed by Ann-Marie Kerr and staring Margurite MacNeil, Sherry Smith and Margaret Smith, produced by Mulgrave Road Theatre and touring to Guysborough, Sackville, Halifax and Sydney in October.