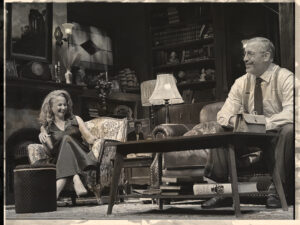

david storch and andré sills

photo by john karastamatis

I was in grade twelve on September 11th, 2001, my classmates and I were just beginning our Twentieth Century History course and I remember feeling as though, without warning, my whole world had just been launched headlong into one of the glossy pages of my History textbook. Having studied Canadian history (pre 1600s-1945) in grades seven and eight, Ancient History in grade ten, and British/European History (1066-1885) in grades nine and eleven, we didn’t have any context for the global calamity that was evolving before our eyes. With almost one hundred years worth of world history to cram into five hours a week for nine months, it was inevitable to me that we would run out of time in History before reaching the present date. Our teacher had to be selective in choosing which historical events would be most pertinent for twenty young women in Halifax to learn on the cusp of the Twenty-First Century amidst a newly Christened “War on Terror.” Rwanda definitely slipped through those cracks. We focused ardently on both of the two World Wars, studying the Holocaust and the creation of Israel and launching into The Cold War and the ensuing conflicts in the Middle East between the Palestinians and the Israelis. We learned about Afghanistan’s significant role in The Cold War, the rise to power of Saddam Hussein and the Gulf War. It is fascinating to me that although I was only five years old during The First Gulf War, I had some knowledge from what I overheard on television of who Saddam Hussein was and that he and Iraq were getting into big trouble and yet, on the other hand, I was nine during the genocide in Rwanda and I remained entirely oblivious to it until far too recently.

J.T. Rogers’ play The Overwhelming (2004), produced by Studio 180 and performed at the Berkeley Street Downstairs Theatre until April 3rd, 2010 is a play that examines an invisible Rwanda, a place where, arguably, even God has turned his back and the dichotomies that arise when the rest of the world is not watching. The play centers on an American Academic, Jack Exley, who is desperately vying for tenure and traveling to Rwanda in 1994 to research his book on activism and the power of the individual to elicit change in the world. He brings his wife, Linda, a personal essayist vying to capture the “truth” of individual’s stories, and his son Geoffrey, a grade twelve student still adjusting to life after the death of his mother, to Rwanda with him. Robert Crew at The Toronto Star found this premise entirely incredulous. A woman at the production I saw came flying across the theatre vehemently and passionately ranting to her friend about how stupid and tedious Linda and Jack were, advocating that they both deserved a smack in the face and that their academic ambitions were entirely rooted in “horseshit.” It’s clear from this behaviour that Rogers had struck some sort of nerve.

I don’t think that The Overwhelming is meant to be a play that emphasizes the stupidity of Americans, despite the fact that in hindsight taking a family vacation to Rwanda amid obvious political turmoil in 1994 does seem like an overtly dangerous decision to make. Instead, the play raises intricate questions about specific Western philosophies and views of the world which surpass North American and European borders. This play was so fascinating to me because I was entirely at the mercy of its characters. I have been conditioned by my education and my own unique set of values to make informed opinions about the historical events of the world from The French Revolution to the Boston Tea Party, but in Rwanda I do not know what or who to believe. Like Jack, Linda and Geoffrey I found myself becoming swayed back and forth between the Hutu and the Tutsis, searching for that moronic Westernized heroes or villains/ victims or bullies classification or, even more terrifyingly, the “lesser of two evils” idiocy.

In 1994 in Rwanda, a country so small the word “Rwanda” has to be written outside its borders on a map with an arrow pointing to it, between 800,000 and 1,000,000 human beings were massacred. The Overwhelming does not simply suggest how horrific and absurd it was that the world in 1994, the same world that preaches so much “We Will Never Forget” jargon when it comes to Holocaust Education, stood by and allowed this genocide to happen, but also how absurd and horrific it would have been if the world had rushed into Rwanda trying to help. It is this message, one that I feel is unique in its stark rejection of idealism, which forces the audience to reflect ardently on the way the Western World has been conditioned to respond to global conflicts and perhaps delve into more conducive thought processes. J.T. Rogers encourages his audience to be critical of Jack and Linda and how narrow-minded they are in the belief that freedom, liberty, democracy and progress are the Band-Aids to heal even the deepest of wounds. Yet, even if we recognize that our philosophies may not translate within different cultures and that we must respect the beliefs, ideologies and fundamental principles of other countries, what is left to root ourselves in when attempting to eradicate an ardent prejudice, history of violence and extreme hatred dating back several generations? How can the thirst for revenge be snuffed out when children are being raped and killed? The questions are, undoubtedly, overwhelming.

The performances in this play are absolutely brilliant in their ability to both personalize each individual character as well as collectively creating a vibrantly sinister ambiance for this portrait of Rwanda. David Storch is stubbornly idealistic as the anxious and zealous Jack who captures a brilliant balance between American entitlement and curiously seeking to learn from every one of his encounters. He walks through the play as though fundamentally believing with understated confidence that he has the ultimate control and ability to incite profound change because he is a learned, white, American male. Storch is exquisite in his ability to unravel Jack as his conviction in this belief begins to waiver. Mariah Inger gives a beautiful performance as his wife Linda, a strong African American female adjusting to her newfound role as Wicked Stepmother and trying to spread pathos like a garden of flowers in the face of an intense ugliness she cannot always see. Inger has a fascinating ability to allow Linda empathy without losing too much of her intrinsic sense of distance and composure. Brendan McMurtry-Howlett gives a charming performance as Geoffrey, a boy who wants to connect and make friends without political implications. Nigel Shawn Williams is compelling as Joseph Gasana, an old friend of Jack’s who has worked as a doctor for children with AIDS and who is now wanted by the Hutu Extremists and Sterling Jarvis is dangerously charming as Samuel Mizinga, one such extremist. Joel Greenberg makes excellent use of space and of his eleven actors continually filling and then emptying the stage to emphasize the strength and safety in numbers and the vulnerability and seclusion that befalls the outsider who does not understand the language.

The paradox that The Overwhelming offers its audience is that while we may search for evidence of all of humanity’s connection with one another and the knowledge that we are “all the same” in attempt to prevent the subjugation, objectification, and oppression of human beings, it is this very assumption that has led to the cultural conquest and destabilization of people across history and all over the world. We all need to open our eyes and to look at the world in a different way, somehow free from the constraints of our various cultures and what we think we know. We are all guilty. We are all complicit to the atrocities that have shaped the modern world. I don’t think the objective of this play is entirely concerned with Jack and Linda and their experiences in Rwanda, but alluding to the massacre on the horizon and not only how the political climate within the country contributed to the genocide but the reactions of the global communities, the knowledge of individuals, and how simply 800,000 people- albeit an entire country- could fall through the cracks in 1994. Linda tells Samuel in the play, “We don’t care about places we can’t find,” and as much as I would like to resist such an unfortunate statement, I cannot help but feeling that I must concede to it. Rwanda fell through the cracks in 1994; who is falling through the cracks right now?

Studio 180’s production of The Overwhelming in association with Canadian Stage plays at the Berkeley Street Downstairs Theatre (26 Berkeley Street) until April 3rd, 2010. For more information or to book your tickets please call 416.368.3110 or visit online at http://www.studio180theatre.com/.