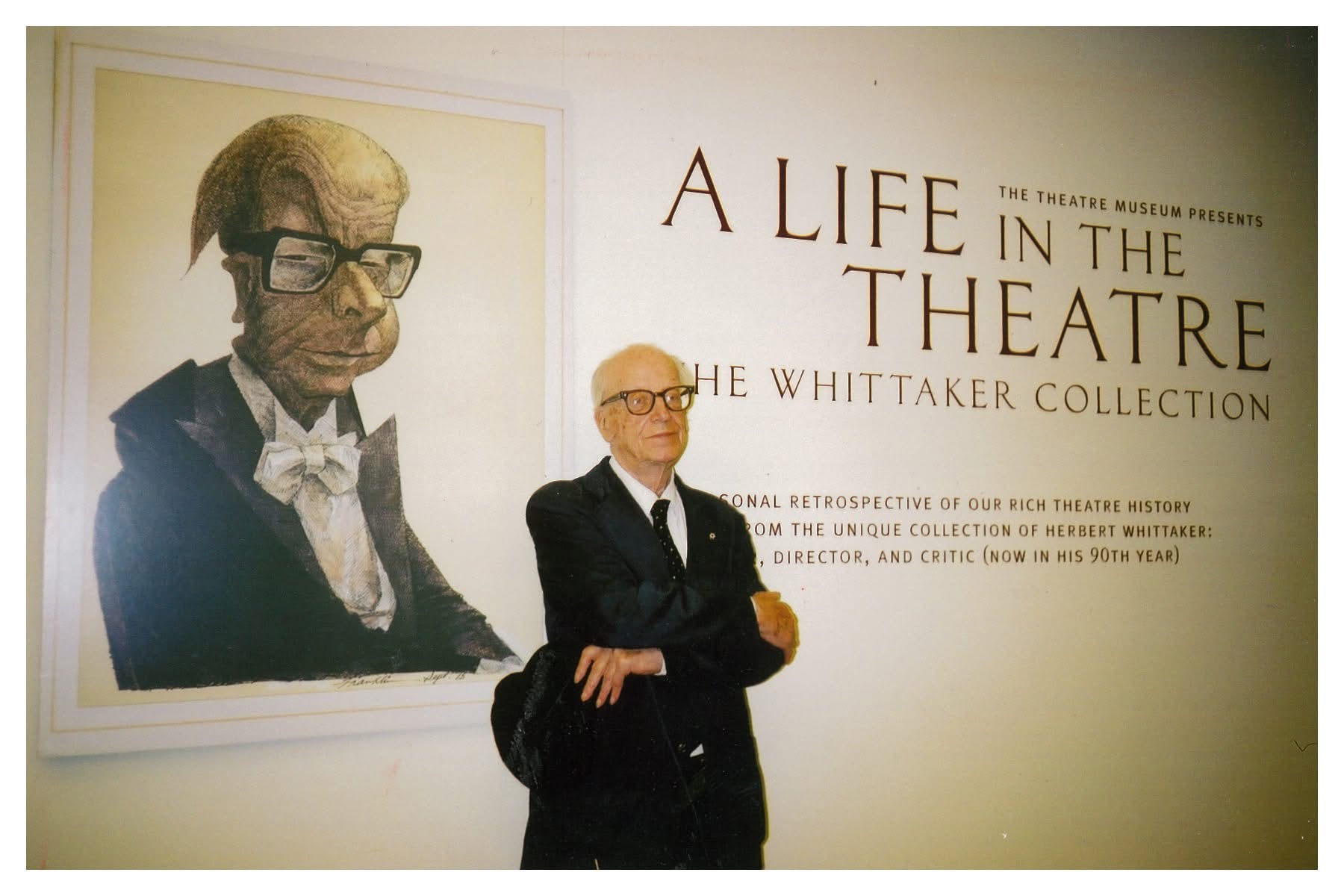

Herbert Whittaker Canadian Theatre Museum

I just finished reading Herbert Whittaker’s book Whittaker’s Theatricals (1993), which is a strange assortment of stories and biographies from Canadian Theatre History that chronicles moments when Canada intersected with some international theatre star that Whittaker had some personal connection with as well.

I have heard Whittaker’s name tossed around from time to time over the years, which makes sense, of course, since he worked as a theatre and dance critic for the Montreal Gazette between 1937 and 1949, and then he began as the theatre critic for The Globe and Mail until 1975. Oddly, though, I have been compared more often to Nathan Cohen, theatre critic for CBC Radio beginning in 1948, and then moving to the Toronto Daily Star in 1959 where he wrote until his death in 1971, and Kenneth Tynan, titan British theatre critic at the Evening Standard (1952-1954), and The Observer (1954-1958 1960-1963). This is interesting because I think, from what I have read, I actually most resemble Whittaker, about whom The Canadian Theatre Encyclopedia says, “[his] criticism was informed by a desire to encourage and promote Canadian Theatre… Whittaker’s advocacy of Canadian drama helped to fashion the theatre scene today.”

In this context, the focus of this book seems strange. Why then write a book about Sarah Bernhardt and Edmund Kean, Elisabeth Bergner, and Fyodor Komisarjevsky? Whittaker was born in Montréal in 1910, and studied theatre design at L’Ecole des Beaux Arts there. He started his career as a theatre designer, working with Everyman Players, West Hill High School, Little Theatre of the YMHA-YWHA, the Negro Theatre Guild, the Montreal Repertory Theatre, and the Shakespeare Society of Montreal. After he moved to Toronto in 1949 he worked with Jupiter Theatre and the Crest Theatre; he also directed shows for the University of Toronto. Coming at theatre criticism from a background in theatre design must have been a gigantic asset to him when writing his reviews. Like George Bernard Shaw he seems to have been a person who was, at least initially, writing about the theatre community from well inside of it, rather than at a purely objective distance.

In this book Whittaker briefly outlines thirty-three theatre artists who are either from away and made some kind of impression, however small, on Canada, or who are Canadian and made an impression elsewhere. He does mention a few examples of Canadian actors who had been making their careers at home, but this is more of an afterthought. There is a tiny thread of autobiography woven into the stories he chooses to tell, but he casts himself as a bit part who keeps popping up in ways that sometimes seem random or contrived. For example, he tells of an interesting moment where he arrives with a CBC technician at John Gielgud’s house to interview him about playing Hamlet, only to find his house empty. When Gielgud rolled up in his car a few moments later he was shocked to see Whittaker and the CBC tech there. No one had told him that the date for the interview had been set. This is a great set up for the story, but Whittaker doesn’t tell us anything about the ensuing conversation, just that Gielgud talked at length and was “astonishing” (179). I would have been very interested to know at least some of what Gielgud had to say…

It astonishes me that Whittaker wrote this book in 1993. It feels like something written in the early 1960s, and I cannot figure out who Whittaker was writing the book for. He gives functional little biographies of each of his subjects, now rendered a bit redundant since the advent of Wikipedia, but seems to write each of the stories with the assumption that his reader has as intimate a relationship with theatre artists, productions, and plays produced between 1930 and 1960 as he does. Even when citing from his own reviews the reader always feels like they kind of had to be there. In 1956, he recalls, Christopher Plummer was cast to play Henry in Michael Langham’s “scheme” for Henry V. What made this production a “scheme”? He doesn’t elaborate. He writes, “In Mr. Plummer… the audience found a crisp, saturnine, magnetic actor. He had the dangerous quality which rivets the attention” (131). This is, without a doubt, a great review- but if the goal of Whittaker’s Theatricals is to really capture this moment in Canadian history for posterity, I would like to know more about exactly what it was in Plummer’s performance that was so dangerous, and how did that serve the play and Langham’s “scheme?” What made this portrayal stand out? He cites similar rave reviews from the works of Ottawa-born actor Margaret Anglin (1876-1958), but doesn’t explain what it was about her that set her apart from her peers. What was she doing differently at this time in history that had critics falling all over themselves to praise her? He writes about the immense contribution of Tanya Moiseiwitsch to the Stratford Festival, but never explains what is so special about the thrust stage. He often references character names but doesn’t name the play, or name drops people by just their nicknames (Timothy Findley went by Tiff, apparently) in ways that are alienating and, frankly, pretentious.

I found the beginning of the book an equal mixture of interesting and embarrassing because Whittaker seems so desperate to make the case that Canada is important too because Sarah Bernhardt once fainted outside the Windsor Hotel in Montréal. It honestly doesn’t matter to me whether Mrs. Patrick Campbell had a life-changing experience in Montréal, what interests me much more is the fact that seeing these (mostly aging) giants of the British theatre during these old road tours obviously had a profound impact on young Herbert Whittaker. In fact, I would have been more interested in hearing more from the younger folks he writes about- like Kate Reid and Plummer- what their experiences were of seeing theatre that impacted them when they were young. Some of the historical tidbits I was most interested in were disturbing. Whittaker mentions briefly John Wilkes Booth’s association with St. Lawrence Hall in Montréal where he apparently met with a group of Confederate sympathizers shortly before he shot President Lincoln at Ford’s Theatre in Washington DC . Hotels in Toronto seem to have been just as bad, as Whittaker mentions an incident where Ernest Rawley comes up against the Royal York when they won’t let Black performers in Toronto to perform Porgy and Bess, headed by Marian Anderson, come in through the front door, lest their American patrons feel awkward about it. These two anecdotes left a lasting impression on me, and warrant further research, for sure.

There is a lot in this book that I found to be a launching pad for further investigation. I know almost nothing about any of the theatre companies listed in Whittaker’s bio, for instance, there are several instances where he speaks of Canadians going to perform in Barbados, some of the actors chronicled I had never encountered before, there were several references to Canadian Players’ Inuit-inspired King Lear, I had never heard about Michel Saint-Denis founding the National Theatre School of Canada, and I didn’t know that the same person who founded our school also founded Juilliard’s Drama Division, and I’d never before appreciated Beatrice Lillie’s close working relationship with Noel Coward. I certainly am overdue to read an exhaustive history of the Stratford Festival.

The weirdest thing about this book being written in 1993 is the nearly complete omission of Toronto’s own theatres- the so called “alternatives” when they were founded- Factory, Theatre Passe Muraille, and Tarragon- but were they still considered “alternative” in 1993? Whittaker speaks a bit about Gratien Gélinas and his huge success with Ti-Coq (1948), but this too is not exactly a contemporary Canadian work in 1993, but he alludes to the ways in which French Canada were developing their own star system, while English Canada continued to look to England and the US for theirs. He doesn’t mention why this has occurred, or what we in English Canada could learn from them, but he yearns for this to be a reality in Toronto, while at the same time, this book is entirely about idolizing stars from elsewhere while looking for England and the US to validate our own exports, like Donald Sutherland and Mary Pickford, before we will laud them too much here at home. I was also interested in hearing a bit about the tensions between French and English at the Dominion Drama Festival, regarding who was asked to adjudicate the plays, how fluent they were in both French and Quebecois culture, and how issues between French and English Canadians more broadly impacted the ways that theatre artists interacted with one another as well. Whittaker raises R.H. Thomson alone out of his generation of theatre artists, and Thomson, who has an association with the theatre critic going back to childhood, writes the foreword for the book. Whittaker doesn’t really make a clear case for why he feels Thomson may be headed for English Canadian stardom more so than others he mentions including Eric Peterson, Gordon Pinsent, and Jackie Burroughs (again, this is 1993!).

I agree, of course, with Whittaker that we do not have a star system in English Canada, although I would say that for those of us theatre kids RH Thomson, Eric Peterson, Gordon Pinsent, and Jackie Burroughs all loom large with equal luminary. The other thing that makes this book feel so dated is the way that Whittaker continually uses sports language depicting a stressful theatrical world where actors were continually “vying” to be the best, in direct competition with one another, where critics decide who has “scored” and thus “survived,” and who has “lost.” Of course, the early 20th Century was a time of gargantuan new ideas and theatre theory, and thus directors (or actor/managers) often objected vehemently, nearly on moral principle, with the style in which others were envisioning these plays. It seems to have been a time when folks were very quick to dismiss something as being “wrong” or herald it for being “right,” rather than appreciating that art is subjective.

Whittaker also throws in some anecdotes that are just mean-spirited gossip, mainly about the female-identifying actors mentioned, as men flippantly comment on their physical appearances, especially as they dare to pass forty years old without spontaneously combusting. The fact that Whittaker includes these, for no particular reason, is another reason why the book feels so dated. I cannot imagine folks a generation younger than Thomson, like Megan Follows or Sandra Oh, reading those stories in 1993 without rolling their eyes.

It’s obvious that Whittaker wasn’t writing Whittaker’s Theatricals for Follows, or Oh, or for me, which is strange- why write a Canadian history book if not for future theatre artists and theatre historians- for future theatre critics? Why only write it for your own friends and colleagues who were there with you as many of these events transpired, and who can fill in all the many blanks to create a complete memory of the story?

This book seems to be a missed opportunity to bridge a large chasm between Herbert Whittaker’s experience in the Canadian Theatre and mine. I do, however, appreciate the roadmap for further research he has left with me here. I don’t feel as though I got to know him very well in these vignettes, but his enthusiasm for the theatre shines through and, of course, resonates with me. R.H. Thomson’s takeaway in his foreword is to reflect on all the talent that has passed out of Canada because there was no infrastructure here, there was no support system, there was no money in it… and wondering what this country could look like if they had all stayed and had been able to have comparable careers here.

That to me seems like the most timely reflection, as I have been wishing every Canadian artist living in the United States would come home, for their own safety, and I have been fantasizing about what it might look like if we had a theatre, film, and television industry for them to truly come home and stay home for. In this way, R.H. Thomson’s musings in 1993 are nearly identical to mine on this Canada Day in 2025. “What a country we have here in our home and native land,” Thomson writes (14). It is even more true as I write these words.

We can’t be looking to the US or the UK any longer. It’s well overdue to be our time and I think Herbert Whittaker would agree. Let’s all get to work.

You can find Whittaker’s Theatricals from Canadian Play Outlet.

Incoming search terms:

- https://www twisitheatreblog com/?tag=megan-follows