Burgandy Code Costumes by Diego Cavedon Dias Puppets designed by Diego Cavedon Dias Photo by Memo Calderon Photography

In Ken Schwartz’s poignant and entertaining new play Quixote!, adapted from Miguel de Cervantes’ 1605 novel The Ingenious Gentleman Don Quixote of La Mancha, which plays at Ross Creek Centre for the Arts until August 16th, 2025, we are introduced to a Spanish troupe of travelling players who perform their plays outside and use a mixture of puppetry and “live action” to bring Cervantes’ epic adventure to vivid life.

Schwartz has distilled the novel down to a very funny 90 minute play, choosing stories to tell that focus on the relationship between Alonso Quijano, a man born into the lowest nobility class in Spain, who is a voracious reader of chivalric romance novels to the point that he decides to give up the stability of his life and pretend to be a medieval knight-errant named Don Quixote, and Sancho Panza, his neighbour, a farmer and family man, who he convinces to travel with him as his squire. Quixote comes to convince himself fully of this fictional quest, seeing the world through a romantic medieval lens where damsels in distress are being menaced by giants, dragons, and wild beasts behind every corner. Panza, however, plays along out of affection for the older gentleman, conceding at times that Quixote’s delusions make the world more interesting and adventurous, but also having to risk his own life in attempt to keep Quixote safe from perils entirely of his own making.

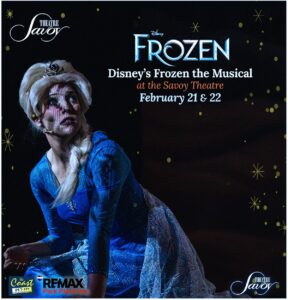

Who better to play a character who is so nobly sure of his mission that he will justify going to battle, and being soundly beaten, by a windmill, but who has an endless trough of both optimism and fatalism, and who is, by all logic, a complete menace, but in such a loveable way you understand why Panza refuses to leave his side, than Burgandy Code? Similar to when she played the equally incorrigible Toad in The Wind in the Willows (2023), Code has such a gift for playing characters who are unabashedly functioning at a cartoon-level of hilarious absurdity, but who are also absolutely oblivious to how strange they seem to others. Code’s Don Quixote grabs every opportunity with gusto, whether that be avenging imaginary injustices, or the way he loves Sancho and his imagined Queen Dulcinea with utter purity of heart and intentions.

Santiago Guzmán plays Sancho Panza, and he is also perfectly cast in this role. We see that he is primarily motivated by a kind hearted desire to help his neighbour, Alonso, but that he is drawn more into Quixote’s worldview by his own desire both for adventure and also the promise of his own property, which Quixote dangles in front of him when he needs to be coerced to do something especially foolhardy. Yet, mostly we see the shining spirit of someone who cares deeply about their friends’ wellbeing and also who wishes that he too could transform a cruel and passionless world into something whimsical and exciting.

The two other characters who move the audience just as much as Quixote and Panza are Quixote’s old and terribly infirm horse, Rocinante, and Panza’s expressive donkey, Burro. Both these animals are portrayed by beautiful puppet heads, designed by Diego Cavedon Dias, with their bodies acted out physically by the ensemble members who take turns puppeteering them. Hilary Adams spends a lot of time puppeteering Rocinante, and is especially skilled at eliciting pathos from the audience for the loyal horse who, despite being emaciated and nearly blind, is as loyal to Alonso as Sancho Panza is, regardless of how physically gruelling it is to keep up with her master. Becca Guilderson often puppeteers the younger Burro, giving him a lot of mischievous, and also impatient, exuberance. Puppets of Quixote and Panza are also used to depict the famous battle with the windmill scene, which roots us in the meta-theatrical conceit that we are watching a production performed by travelling players. The puppets are sort of Punch and Judy adjacent; they could be Spanish relatives of Lady Elaine Fairchilde from Mr. Rogers’ Neighbourhood, although they are full-bodied puppets, like marionettes, yet without strings. This gives them a timeless feel, connecting to the world of the novel written in the very early 17th Century, but also as familiar to the much more recent Millennial childhood. There is also a lion, played by Hugh Ritchie from beneath a large lion puppet head, that is also exquisitely performed.

Hilary Adams plays a very memorable lion trainer character who attempts to appeal to Quixote’s non existent rationality, and the usually sweet and affable Henricus Gielis becomes terrifying as an offended muleteer out for blood. He reminded me of either Stromboli from the 1940 Walt Disney Pinocchio when he loses his shit on the hapless puppet, or one of the Royal Guards from 1992’s Aladdin. Gielis, along with Guilderson, and Omar Alex Khan, also provide some Spanish guitar that further roots us in time and place. Allen Cole is a Musical Consultant.

I enjoyed the conceit of the Spanish players; we hear them each say their own quirky names, which makes them sound adjacent to Shakespeare’s mechanicals, but I was a bit curious about where we were in time- is this a contemporary troupe, are we seeing a theatre tradition from one hundred or two hundred years ago, or is this story much more contemporary to them than it is to us? The costumes, also by Diego Cavedon Dias, are a sort of ragtag amalgamation of colourful layers that are meant to showcase the budget for the fictional players, but also conjure up images that the audience has of both Hispanic culture, and also the tunics and leggings involved in depictions of knights. Code’s kitchenware armour is hilariously rendered here, especially her coal pail helmet, which keeps falling off. She very much looks like a child’s imagining of a knight, alluding to the fact that Quixote very much has a childlike innocence and sense of wonder as well.

Ken Schwartz directs the play, which takes place in a meadow very close to where the fire pit is set up for the late night show, keeping Burgandy Code and Santiago Guzmán very much centred throughout most of the action, with the ensemble moving around them- as though they are the centre of the tornado that sucks everything in towards them and then invariably leaves behind a mess for someone else to clean up. Schwartz mentions in his programme notes that what is so notable in this story is how two men who see the world so differently, who cannot agree on what is fact and what is fiction, even when it seems like madness to reject what is objectively the truth, can remain so loyal in their friendship. This is obviously an apt observation for the times in which we are living, where people are deeply divided along political lines, and family members are having to ask themselves how they can maintain relationships with loved ones who don’t seem to be living in the same reality as they are. I also couldn’t help but see the more cynical side of this as well, especially in the scene where Quixote attacks and maims an innocent man, played by Hugh Ritchie, because in his delusion he mistakes him for being a villain. Quixote’s fantasy world can be both fanciful and dangerous, not just for himself, but, importantly, for others who just happen to find themselves in his way. In these moments Panza is in never-ending damage-control mode, putting out the fires that Quixote leaves in his midst, and this too is indicative of what it is like to live in Canada in 2025 when we know so many of the emperors with the most power in this world have no clothes, and imagination far too often tips over in conspiracy theories that, from multiple different angles, put us all at risk of being Ritchie’s character with the cart.

It is interesting that in this adaption we see this scene twice, and I think the audience laughs at it both times, because we are encouraged to see the absurdity in it, and it is empowering to be able to laugh at what is frightening and infuriating in our own lives. But we are being reminded that Quixote is not without his casualties. Sancho Panza is an extraordinary friend to Alonso Quijano throughout the entire play, but Quijano is only really able to unselfishly put Panza’s wellbeing first when he returns to himself at the end of the story. This, really, I think speaks volumes about where we are at, unfortunately, with those in contemporary society who are perpetually tilting at windmills.

Quixote! and The Haunting of Sleepy Hollow run until August 16th. Quixote! plays Tuesdays and Wednesdays at 6PM, Saturdays at 4PM, and Sundays at 2PM. The Haunting of Sleepy Hollow, plays Tuesdays, Thursdays, Fridays, and Saturdays at 9PM. Tickets range in price from $15.00 for children, $25.00 for students/artists/unwaged, $35.00 for adults. You can get yours here or by calling 902.582.3073. There’s also seat upgrades available and picnic options. Babes in arms can see the show for free.

For one night only (August 24th at 6:00pm) Icarus, the Falling of Birds by Gale Force Theatre will be presented as a Pay What You Can event with limited seating.

Ross Creek Centre for the Arts is wheelchair accessible, and there is a golf cart available for those who may need help moving around the outdoor space. Please let the staff know when booking your tickets if you need wheelchair accessible seating or will require the golf cart. Sunscreen and bug spray and dressing in layers is advised for all theatre patrons. For more information about what to expect when you arrive at Ross Creek please visit this website.