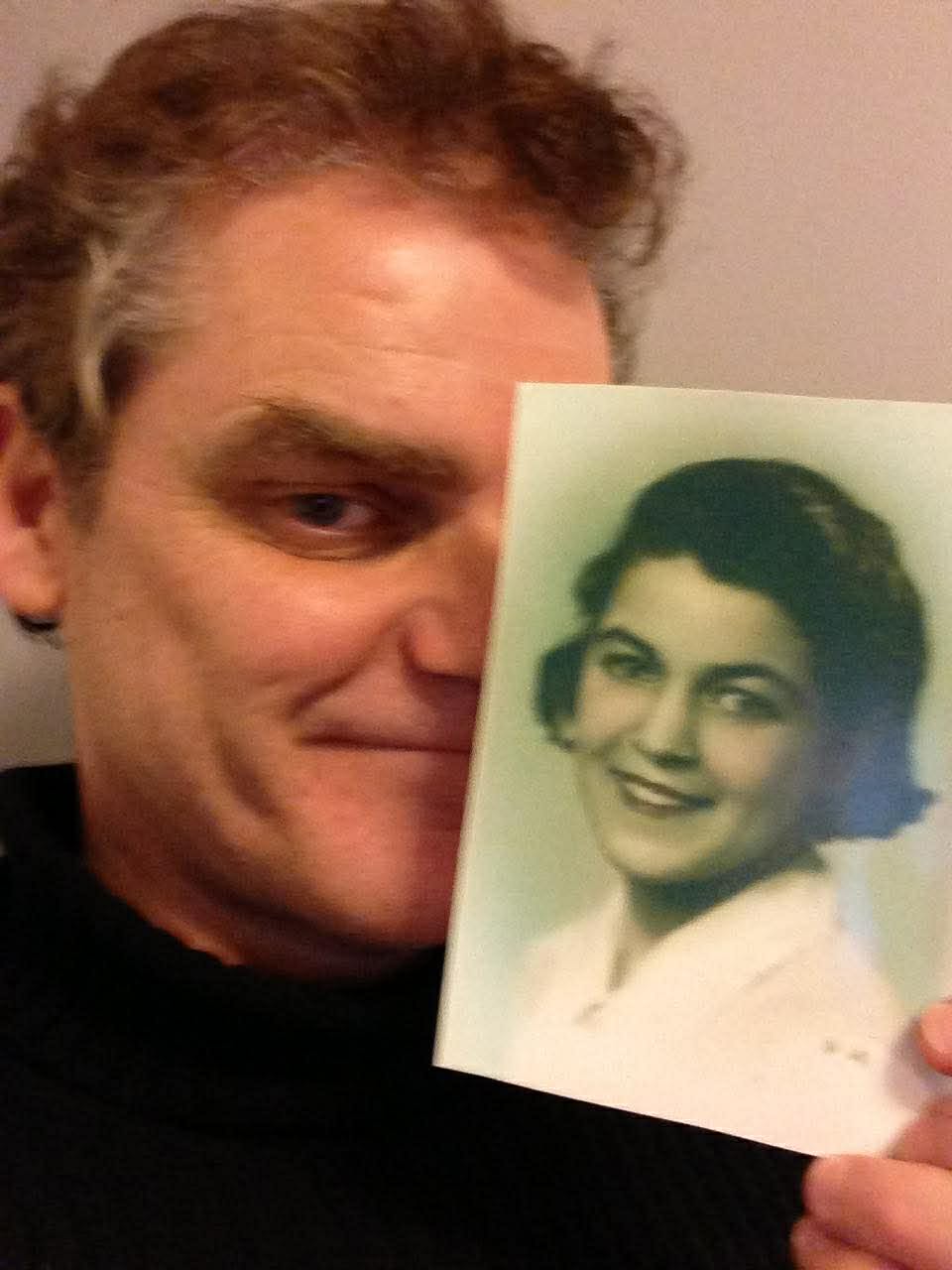

Shawn Wright holds up a photo of his mother, Regina Robichaud Wright

In the early 2010s Shawn Wright would sit with his mother, Regina, in the nursing home where she lived in Saint John, New Brunswick while she watched Murder She Wrote. Shawn Wright is the youngest of seven siblings and they were taking shifts spending time with their beloved mama at the end of her life. His shift just happened to be during her favourite show. “She said I wasn’t allowed to speak while Angela Lansbury’s speaking. So we can only talk during the five minute [commercial breaks].” And yet Wright found the things that his mother was saying during these short intervals so hilarious that he started to write them down, and he often shared little snippets with his friends on Facebook. “I thought it was a way just for me to deal with her mortality. I thought, ‘Oh, it’s so fucking funny what she’s saying.’ And it was never as a bit. She was dead serious. All her pontifications. And then I’d wake up the next day [look at my Facebook post and have] 600 comments.”

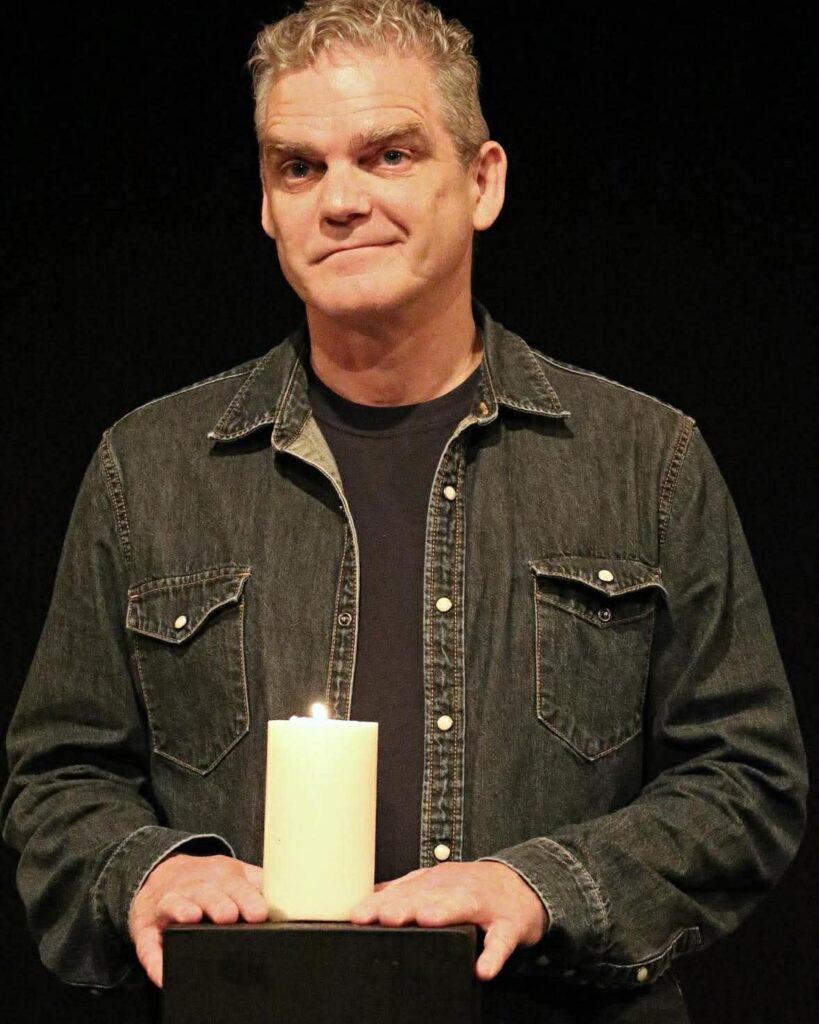

He didn’t know what it would become, but he kept writing down these hilarious short quotations from his mother, and eventually the work turned into his play Ghost Light, which opened at Theatre New Brunswick in November of 2016, and is back there for a short run from January 28th to 31st produced by the Atlantic Repertory Company. I was so happy to get to chat with Wright about this play via zoom last week.

Regina Wright (nee Robichaud) was born to be a performer. She was born in the mid 1920s in Saint John, and as a child she would invite audiences in to watch her perform in plays in her barn. “I think she was eight when she played Medea,” Wright says, “She was not daunted by parts… it was truly the equivalent of a kid having a lemonade stand and the community thinking, ‘we should go see Regina’s shows,’ but they were always about middle aged women at their wits end, just trying to fucking cope- never about kids… she was always the star… she knew even then how to concoct a good arc for herself so that she could be the hero at the end.”

When she was rehearsing Regina would also set up her collection of dolls (that her father, who burned garbage at the dump, would salvage for her) to be part of her audience. She would also recruit her siblings to be audience members. In telling these stories to her son later she would stress the impressive size of her early audiences- as many as 30 people- and Wright says, “and I’m thinking, ‘Mom, like 26 of the “people” were dolls’ [and she would counter with], “Oh yeah, but, you know, you see their eyes and you want to do a good show for them.’… and then you wonder why I’m, like, cracked,” Wright jokes.

Even after getting married and having seven children Regina didn’t give up on her dreams of being on stage- she became a passionate member of the St. Rose Parish Players, and seeing his mother perform in these community theatre plays became a formative experience for Shawn Wright.

The Parish Players were a “ragtag bunch of folks”- a lot of women who were raising kids who got together to rehearse and perform a series of plays in Saint John before there was much professional (or amateur) theatre there at all. Often they needed children to be in the plays, so they would recruit their own, like Wright’s older brother and sister, and sometimes from the neighbourhood at large. “My mother played this part where she had a bunch of kids out of wedlock, and this is the sixties, right? So all the neighbourhood kids were playing all her kids.” Regina didn’t just act in the plays, she also wrote many of them, including one play that included “an interracial romance.” “I didn’t even know one Black family in our whole Western part of Saint John, but somehow she found a Black man that was interested in theatre and his daughter, he got her to be in the show” and she played the daughter of the interracial couple. Wright notes that this was quite scandalous at the time, especially coming from his mother, a married woman. “My father was there in the front row, and I would sit with my father watching it,” he says, “I was like, ‘why is our couch on the stage?’”

Since Wright was the youngest in his family he wasn’t in school yet so he would often go to the afternoon rehearsals with his mother and sit on a trunk of props and watch. “My mother was a pillar of the church, she was so sweet… and [there] she’d be playing whores and murderers and stuff.”

Beyond the shows that he saw at the St. Rose Parish Players and a deep love for the film version of The Sound of Music (1965), Wright didn’t have the opportunity to do much theatre or see much theatre until he was in High School, and then in University in Fredericton where he joined a theatre group, and then he performed as part of the Theatre New Brunswick Young Company. Once he graduated he left New Brunswick and went to Toronto, and he’s been working as an actor ever since. After his run in Ghost Light he’s returning for his 10th Season at the Shaw Festival in Niagara-on-the-Lake.

In Halifax audiences were riveted by Wright’s performance in Jamie Bradley and Garry Williams’ play Kamp at Neptune Theatre back in 2018, but he was also here early on in his career in productions of A Christmas Carol, Evita, Joseph and the Amazing Technicolor Dreamcoat (where he played the Pharaoh), Alice in Wonderland, The Secret Garden, and Les Misérables. “I love it there, of course,” he says.

After his mother’s death, back in Stratford, Wright took a Memoir Writing class and found that while his writing there was separate from the notes he had taken while watching Murder She Wrote he was still writing more and more about his mother. He was headed back to New Brunswick for his niece’s wedding shortly after Thomas Morgan Jones became the Artistic Director of Theatre New Brunswick, and thought it would be a good idea to meet him while he was home. Over coffee Jones noticed Wright’s notebook and asked about it, and Wright mentioned that he had been writing down some things about his mother. “He said, ‘Well, what’s her deal?’,” remembers Wright, “And then I said, “Oh, I haven’t really thought about it that much.’ … And [then] I talked for two hours.”

Jones suggested that Wright delve deeper into this work and offered to send him some writing prompts that might help facilitate the process. Wright had seen a one person play that Jones had directed at Theatre Passe Muraille in Toronto written and performed by Anusree Roy that he had found “so riveting.” Wright was expecting these prompts to be direct questions about his mother, but instead he says, stressing that Jones is the “sweetest man,” one of them was “name three things that in your private heart you’re most ashamed about, and then write another page on what that has to do with your mother.” “I’m like, bitch this is a comedy!” Wright laughs.

Wright says that in working with Jones’ prompts he eventually wrote about various phases of his life, and then Jones kept encouraging him to tie his mother more into the story, and at this point there was no one project in mind, no one form that the writing needed to take, it was just helpful for where he was in his grief. Back in New Brunswick, however, during another meeting over coffee, Jones let Wright know that he had just had a playwright drop out of their upcoming season, and did Wright think he could write his show in eight months? Jones said, “I know that it’s not a show yet, but I want to do this.”

At first Wright was envisioning a play with six actors. “I had originally written it that someone would play my mother at three different stages of her life [and] someone would play me at three stages of my life… the show goes from my mother’s birth, her life without me, our life together, and my life without her.” As he kept developing the script eventually Jones said that he thought there should just be two actors. Jones wanted Wright to play himself. Wright was skeptical, but Jones pressed him, and eventually Wright agreed. “I wasn’t looking forward to that, but I said okay,” he says. Then Jones brought Wright a drink and offered up another idea: Wright should also play his mother.

Jones said that given how specific the stories are that Regina tells he didn’t think Wright would think, as generous as he is, that anyone could really do her justice. Wright had some questions about staging logistics, but Jones had already thought these through. “My only stipulation, which [Jones] thought was a good idea, was I don’t want a costume. I don’t want to like put on a funny hat or a wig or something as her because I didn’t want the distraction from the story.”

The show played in both Fredericton and Saint John, and Regina’s friends from St. Rose Parish Players were in the audience engaging with every word Wright said as his mother. “I’m doing a scene talking about something and I’d say something about… when I threw Claire Graham’s glasses out the window in the dressing room, and someone [in the audience] would say, ‘Oh, Marge, do you remember Claire Graham? Oh, I haven’t seen her… remember when she farted at church?’” All these conversations happening among the audience members he characterizes as chaotic but amazing.

When Matt Murray and Steven Gallagher (playwrights/actors/friends of Wright) came to see Ghost Light in Saint John they encouraged him to submit it for Storefront Theatre’s Solo Sessions: six solo pieces that would be performed in repertory. The hitch was that the deadline to apply was closing in and the performances themselves were only three weeks away. Murray and Gallagher told Wright that they would write and submit the application for him and Ghost Light sold out its run at that festival. An editor from Playwrights Canada Press saw the show there and wanted to publish it as part of an anthology, Q2Q : queer Canadian performance texts. With no promotion behind it Shawn Wright has been performing this show whenever he is available to do it in different places in the country for the past ten years.

“What I have found really interesting is that I find in Toronto… the audience related to me. And when I did it here [in New Brunswick], they relate to [Regina]. I’m the other in the story,” says Wright. He says that folks either “relate to the person who is losing control of their life through age, or they can relate to the person who is negotiating the burden of caring for a parent, while at the same time needing them to be a parent.” He says it’s a different experience telling her story in Saint John because she is so beloved there. “What I find is universal is that she’s a larger than life character and she’s believable. People…. really just like spending time with her… like Dolly Levi from Hello Dolly or Mame or something. You don’t watch that and think, ‘oh, nobody’d ever say that. Who would ever say that to a kid?’ You’re just like, ‘oh, I like her. I’m going on the ride with her because she’d be telling the truth in all the rooms.’”

The Atlantic Repertory Company, headed by Executive Director Stephen Tobias, is one of the main reasons why I wish there was train service between Halifax and Saint John. Ghost Light is the third in their fabulous season this year, which began with Martha Irving and James Dallas Smith in Cottagers and Indians by Drew Hayden Taylor directed by Samantha Wilson. Just before Christmas they had Patrick Jeffrey and Bertis Sutton in Billy Bishop Goes to War (John Gray/Eric Peterson) directed by Mary-Colin Chisholm, and coming up in April they have R.H. Thompson in Henrik Ibsen’s The Master Builder directed by Richard Rose.

The term ‘ghost light’ is a familiar one to those who work in the theatre. It was a concept that Regina introduced her son to when he was very young. Wright remembers, “I was around six years old. It was a hot, humid summer. I couldn’t sleep. I went downstairs and my mother was sewing a pair of pants for my brother, and she could see that I was sweating, and of course we didn’t have air conditioning or anything. It was near midnight and she said, ‘let’s go out for a walk,’ and I was just so thrilled because we were outside. I was in my pyjamas. She was in a house dress. Street was deserted. And we walked through the hollow, which was this beautiful sort of wood, and it was very cool, and we walked past the parish hall where they would do their plays, and it was midnight, and I said, ‘mom, there’s a light on at the parish hall. They must be rehearsing in there.’… my mother said, ‘no, no one’s rehearsing in there. It’s the ghost light.’ and I said, ‘what’s that?’ and my mother said, ‘the last person to leave the theatre at night must leave a lighted lamp on in the centre of the stage’ and I said, ‘why?’ and she said, ‘every theatre has a ghost, a ghost who used to love being on the stage, and when all the mortals are asleep, that sprit follows the ghost light that’s been left for her, and she gets to recreate all the great roles she played in life.’ And then my mother took a deep breath and said, ‘Oh, doesn’t that sound like a wonderful place to end up?’… and so that’s where she is now.”

Ghost Light written and performed by Shawn Wright and directed by Thomas Morgan Jones plays at the Atlantic Repertory Company (112 Princess Street, Saint John) from January 28th to 31st at 7:30pm. Tickets range in price from $35.00-$45.00 and they are available online here or by calling the Box Office at 506.652.7582. Industry Night is January 29th and there are $25.00 tickets available for Arts Community Members.

Hopefully we will get to see this show in Halifax sometime soon.