Melody McArthur as Sandy Photo by Stoo Metz

On Thursday night I went to Neptune Theatre’s Fountain Hall to see Bear Grease, a touring all-Indigenous reimagining of the musical Grease created on Treaty 6 territory, which plays here as part of the Prismatic Arts Festival hot on the heels of a successful off-Broadway run.

The production is not a literal retelling of Grease through an Indigenous lens, but more a tapestry of pastiched moments that are familiar from the musical mixed with original hip hop, songs that aren’t directly from the musical but come from the same era of music, and aspects of the 1978 film directed by Randal Kleiser that were not focal points, but here are explored in greater depth through a completely different lens. It is left up to the audience to reflect on the disparate moments that have been included in this tapestry within the overarching theme of Grease.

Grease was written by Jim Jacobs and Warren Casey and first opened February 5th, 1971 at Kingston Mines, a Chicago nightclub. In fact, not only was the musical a nostalgic homage to the unique High School experience of the late 1950s, but, originally, the musical was set very much in Chicago, and sought to explore the working class youth subculture known as greasers that existed there at that time. The score is modelled on the very early rock n’ roll music that has become synonymous with the 50s, especially in American popular culture.

As the creators of Bear Grease, Crystle Lightning and Henry Cloud Andrade, point out before the show even officially begins, the music that has become so iconic to the 1950s and early 1960s made famous by folks like Elvis Presley originally came from musical genres pioneered by Black artists, and while there are many Black musicians and groups that became household names in the 50s, there are many examples of songs that were written by Black songwriters and first performed by Black singers that were later covered by white artists, and it was only then that the song reached mainstream success. In Grease, of course, the music, is sung by its all white characters, and by the fictional band Johnny Casino and the Gamblers (Sha Na Na in the film, who has one token Black member). We are immediately able to see how the film has whitewashed this music and striped it of a more nuanced and interesting cultural context and history to make it more palatable for the white American audiences of 1971, who were looking back at the very problematic 1950s with nostalgia- in the same way that white supremacists continue to do to this day.

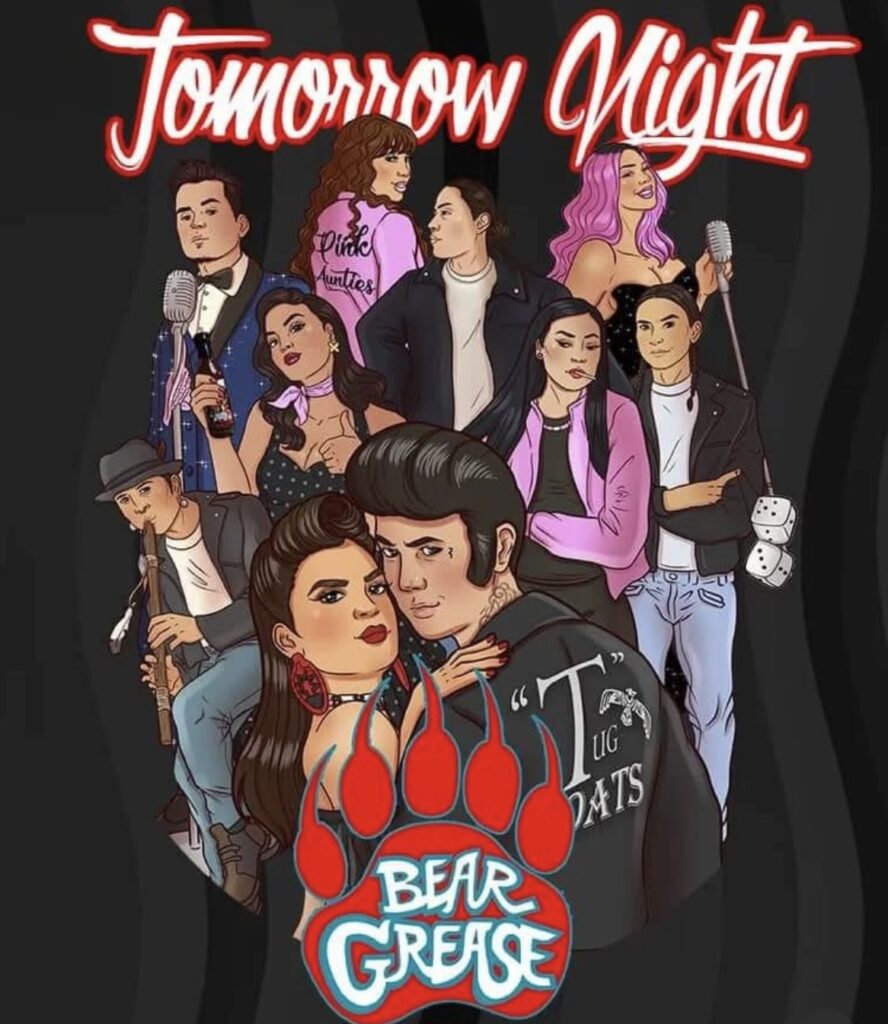

Following this up with the iconic opening animation credits from the 1978 film version of Grease (by John D. Wilson), with Frankie Valli singing the movie’s title song, playing on a cinema-sized screen at the back of the stage, but with each character reimagined as an Indigenous counterpart, and the names of the actors from this production replacing John Travolta, Olivia Newton-John, and Stockard Channing etc., is a powerful re-centring of representation. The opening credits for Grease were beautifully and creatively imagined for the film, and they don’t just provide a cartoon representation of the lead actors, they create a whole 1950s nostalgia world that absolutely grounds the film in this specific memory of the decade. In Bear Grease the animation is incredibly, gorgeously accurate to the original, and, similarly, grounds the show in a very specific and rich portrait of both contemporary life for Indigenous folks on Turtle Island, and also a whimsical imagining of what that might look like if transported to the 1950s- free of the gruesome historical realities faced by Indigenous people at that time.

In re-watching the original animation from the film I am now noticing that not only are all the actors white, in a sequence that is absolutely laden with specific pop cultural references meant to immerse the viewer in 1959, there is only one figure who isn’t white- a Black man whose identity isn’t immediately clear to me. Meanwhile, they have Elvis representing rock n’ roll, and they also have a representation of Davy Crockett, referencing the five-part Walt Disney serial that aired in 1954 and 1955. The real history of Crockett, his political legacy, interactions with Indigenous folks throughout his life, his views on slavery, and his demise at the Battle of the Alamo, are complex, contradictory, disturbing, and confusing, and all of this, of course, was deflated and wrapped in an American flag for children by Disney, completely watering down and twisting history until it was basically unrecognizable from the truth. Sandy in the opening credits is depicted as a Disney Princess who woodland creatures visit and help her to get ready in the morning- conflating Olivia Newton-John with Cinderella, released in 1950, and Sleeping Beauty (1959). It also reminds us that when the film version of Grease was made all Disney’s princesses were white.

The allusion to Davy Crockett also reminds us of the realties faced by Indigenous people both in 1959 and also in 1978, and, of course, just putting a cast of imagined Indigenous characters in a Rydell High School setting is powerful because we know that in 1959, as in 1978, most Indigenous children who should have been attending ordinary High Schools with Sock Hops and poodle skirts, grabbing burgers and milkshakes from the diner before heading home to do their homework or having a sleepover party with their friends were at horrific residential schools, separated from their mothers, fathers, and even the siblings who went to the same school as them, in attempt to completely divorce them from their heritage, culture, and language. We are reminded of Chanie Wenjack, who was born just five years before Grease was set, and who died twelve years before the movie came out at the age of twelve attempting to escape from school in Kenora, Ontario. If Wenjack were still alive as he should be he would be the same age as John Travolta.

Through a humorous focus on a very brief Ipana toothpaste commercial meant in the film to showcase Jan’s good natured self-awareness as she compares herself to Bucky Beaver, Bear Grease also touches on how Indigenous peoples have historically been depicted and used in advertising and branding to sell commercial products- they use an American ice cream brand that used to contain a slur for Inuit in their name as an example, but it also conjures up images like Chief Wahoo, the Land O Lakes butter label, and the statues of Indigenous people that we associate with cigar stores. All these images, like Davy Crockett, like the concept of playing “cowboys and Indians-” also indicative of a 1950s childhood- store up problematic stereotypes and connotations in our brains, that are often reinforced in media over decades.

As we see the Indigenous characters in Bear Grease, Danny, played by Bryce Morin, and Sandy, played by Melody McArthur, meet and fall in love at the powwow, only to reconnect at school, like their Grease counterparts, where Danny embarrasses Sandy in front of the Pink Aunties, suggesting that their connection that summer didn’t leave a lasting impression on him, it highlights how rare it is to see Indigenous characters in this cultural context- as two teenagers whose biggest concern is whether they fit in okay at their new school, and whether they are perceived as cool by their peers. Danny and Sandy aren’t contending with inter-generational trauma, they are given the gift of inter-generational joy and culture. They are allowed to just be two kids with crushes on one another- a privilege white teenagers have been afforded on screen since cinema was invented.

Within a framework that holds weighty issues and profound insights the musical itself is mostly silly, crammed with loving and funny references to life on the reserve, a plurality of Indigenous cultures, and experiences, and a lot of fun and joyfulness. When Morin’s Danny sings “Hopelessly Devoted to You” with a drum in the style of a Round Dance, and when Tammy Rae Lamouche as Rezzo sings “Wichihin” (“Stand By Me”) gorgeously in Cree, I think audiences notice how rare it is to hear these English songs reimagined through an Indigenous lens, because we know that, especially for most of the past 158 years, white Canadians have done everything in their power to completely eradicate Indigenous languages from this land. Every Indigenous person in this country who speaks their language, keeps their language, can learn their language or teach their language is a miracle, and so getting to the point that pop music can be translated and sung and reimagined within an Indigenous context is innately poignant and celebratory. The layering, as well, of the Cree and the English together, is symbolic of the way we as Canadians like to think of ourselves, as a mosaic, and we are, thankfully, doing better at collectively honouring that diversity of language, of culture, and, certainly, at the heart of the proverbial mosaic should be the bedrock of Indigenous languages that were born out of these lands and that reflect and know this beautiful place the most intimately.

There are a few new songs that have been created specifically for Bear Grease that are done in a hip hop style, similar to the way Lin Manuel Miranda famously uses a mixture of contemporary musical theatre and hip hop in his musicals. This connects the characters in Bear Grease loosely in an imagined 1959 with the reality of 2025, and implied are the generations worth of incredible resilience and strength that link the two. It also shows a more respectful sharing of musical art forms between two historically marginalized groups in contrast to the whitewashed rock n’ roll that defines Grease.

The company is made up of very talented singers and dancers. I really liked how the T-Birds especially (Rodney McLeod, Raven Bright, Mikey Harris, and Brandon “Bamm” Roberts) really capture the frenetic and goofy spirit of teenage boys, especially in their dancing. Bryce Morin and Melody McArthur have huge beautiful voices that lend themselves perfectly to the doo-wop influence in the musical’s rock n’ roll score.

The ending of Grease has been criticized in the last few decades for having Sandy peer pressured by Danny, his friends, Rizzo, and the overall greaser culture of their school to abandon her homey conservative style and to dress instead in a highly sexualized manner, as though fulfilling Danny’s girlfriend fantasy is more important than being her authentic self. In Bear Grease Sandy asserts her agency and decides for herself how she wants to dress. Whether she decides on a jingle skirt or tight leather pants, neither make her more or less herself. Again, we can see this in stark contrast to the realities of residential school, where children were stripped of their own clothing, often in favour of uniforms, as we know from Phyllis Webstad having her brand new orange shirt taken away from her at the Mission School in 1973. This eliminated the Indigenous children’s ability to have any agency, to express themselves and their own individuality, along with, of course, estranging them from their culture and the familiarity of home.

In the moment in the theatre I found Bear Grease to be unexpectedly and continually moving in a way that at first seemed at odds with how light and cheeky the show’s humour and overall spirit was. In many ways the vibe mirrors its source material, where Danny and Sandy fly away in a car into the sunset at the end, but the more that I have broken down the specific focuses of the show the more I have come to understand why I found it such an emotional experience along with being a fun one. Bear Grease is very much like a living, singing, dancing collage, where the audience gets to choose whether they want to stand back and appreciate the overall picture, or whether they want to come in really close and look at each element that was chosen individually to get a stronger sense of the theme. The focus in Bear Grease is on Indigenous joy, Indigenous talent, reclamation of identity and culture, and especially Indigenous humour. The darker shadows of history are much more subtle, and are being subverted by the joy, by the humour, by the triumph of this cast and crew being here, in Kjipuktuk, performing this show for us here on Neptune’s Main Stage.

I am also left wondering what an original fully Indigenous musical about two high schoolers maneuvering through “young love, peer pressure, friendship, teenage rebellion, and sexual exploration” set in any decade might look like. And, more importantly, who is going to write it.

Bear Grease plays just twice more at Neptune Theatre’s Fountain Hall stage as part of the Prismatic Arts Festival: Tonight, October 4th at 7:30pm and tomorrow October 5th at 2:00pm. Tickets are limited, so grab yours online now, or call the Box Office at 902.429.7070 or visit the Box Office in person at 1593 Argyle Street in Kjipuktuk/Halifax. Once the show is closed here Bear Grease will tour to Charlottetown’s Confederation Centre of the Arts, the Capitol Theatre in Moncton, the Fredericton Playhouse, and the Imperial Theatre in Saint John, before heading to British Columbia. For more information about these shows please visit this website.

Prismatic continues in venues throughout the city just until October 5th, 2025. For more information about their programming please visit this website.

Neptune Theatre is fully accessible for wheelchair users. For more Accessibility Information Click Here.