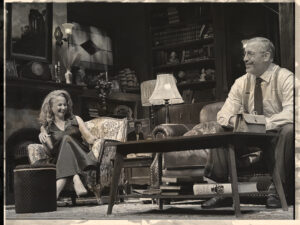

Photo by April Maloney

The Sipu Tricksters from Sipekne’katik First Nation in association with ZUPPA have brought Metu’na’q, an adaptation of William Shakespeare’s play The Tempest to a cozy little clearing just off a short pathway that branches off from Arm Road in Point Pleasant Park. The adaptation centres Caliban’s experience. He is a character continually referred to in animalistic terms by the other characters in the play. He is called fish, moon-calf, and monster most frequently. For his part, Shakespeare never tells us definitively what Caliban is; we are just told by Prospero that his mother, Sycorax, was a witch from Algiers, and she has died before the action of the play takes place. In this production Caliban is very much a bright eyed young human being, played by Bella-Rose Masty, an Indigenous inhabitant of the island where the play is set who has been enslaved by European sorcerer Prospero for the past twelve years, and he is determined to be freed by any means necessary.

Director Ben Stone has moved the plot about Caliban seeking his freedom, and attempting to recruit two Europeans who have just recently been shipwrecked on the island to help him be rid of Prospero once and for all, to the forefront. This reduces the plot of how Prospero used his own dark magic to create a storm that washes his brother, Antonio, King Alonso of Naples, and the King’s son, Ferdinand, along with their shipmates ashore, to get revenge on Antonio, who is the person who had him and his daughter Miranda banished from Milan to this island in the first place. We see this action through Caliban’s eyes. Caliban doesn’t care why these new Europeans, Stephano and Trinculo, have come to the island, he is just focused on figuring out how he can use this new series of events to his advantage.

Caliban is not the only Indigenous character that we see. Ariel, played by Emerald Paul, and their Spirit Ministers, Heather Knockwood and Sheena Marie McCulloch, represent the spiritual magic inherent to the island, which has also been harnessed and exploited by Prospero, as he uses Ariel for both his own machinations and also as a way to discipline the more rebellious Caliban.

Ben Stone stages the production with the audience seated on wooden benches surrounding the action on two sides, with playing space on the two other sides forming an oval. Ariel and the Spirit Ministers often retreat from Prospero’s immediate sphere of influence into the woods, and we see the lost Europeans, Stephano and Trinculo, wandering around in the woods as well, both before and after they encounter Caliban. Setting Metu’na’q here in the park roots the play so beautifully on the land, which is of such importance here. The Tempest was written between 1610-1611; it is the last play that Shakespeare wrote on his own, and it is strikingly modern in that it reflects a recent watershed moment: England establishing its first colony, Jamestown in Virginia (on the land of the Paspahegh), in what is today North America, in 1607. A few years earlier, of course, the Mi’kmaq helped French explorers, led by Samuel de Champlain, survive their initial winters at their settlement of Port Royal (Nme’juaqnek) beginning in 1605. Shakespeare died in 1616 at the age of 52, so he is writing about momentous societal change from the vantage point of a middle aged English writer and actor nearing the end of his life. In The Tempest Prospero has not come to this island of his own volition with plans to conquer it like Edward Wingfield, the first Colonial Governor of Virginia, Prospero has been banished here, and thus sees it as a kind of prison or purgatory that he must endure, with his ultimate goal of returning to his hometown of Milan and being reinstated as Duke there. In this way, while the early settlers in Jamestown, Virginia were looking at the land lustily, dreaming of all the riches they could plunder and the settlements they could build, Prospero sees Caliban and Ariel’s island as a wasteland of barbarity. It is only through Caliban that we hear an accurate portrait of how visually stunning our real surroundings are. In both cases, the Europeans treat the land with disrespect, and as a commodity only to be used up for immediate profit. It is even more sadly apt to be sitting in Point Pleasant Park taking in this story during a woods ban due to climate change, uncharacteristic wildfires, and the continual loss of the hearty, diverse Wabanaki-Acadian forest. All of this is a result of human activity and, more overtly, the same capitalistic obsessions that drove King James I, the monarch who oversaw England’s first colony, and those first settlers in Jamestown.

While Stone roots Metu’na’q in some ways in more realism, having Caliban and Ariel be played as Indigenous humans and not supernatural creatures, for example, there is still an element of magical realism and sorcery inherent in the play. Prospero, played by Janine Adema, has a powerful book that gives him magical powers. He is able to use these powers both to create the storm that brings his brother, the King, and Prince ashore, but also the book is the source of his ability to harm Ariel and Caliban if they don’t do his bidding. He is not able to keep them enslaved without it. Is Shakespeare alluding here to the immense powers that come from knowledge, from education- that it can both help you move proverbial mountains in the pursuit of justice, while also being able to corrupt you horrifically? Is it Prospero’s knowledge that creates the racist hierarchy between himself and those who he doesn’t consider to be ‘civilized’ like himself? Other magical aspects of the play remain mysterious. Prospero claims that he rescued Ariel from being entombed in a tree, where he was imprisoned by Caliban’s mother, Sycorax. In this version I think the audience is more likely to be skeptical of Prospero’s version of events concerning both Ariel and Sycorax, but we can only speculate on what the truth might be.

Adema plays Prospero as drunk on his own power, like a raving Faustus, giddy with the ability to send Ariel to do his bidding, like the Wicked Witch of the West dispatches her flying monkeys, but, conversely, he has utter contempt for Caliban, who he tasks with more gruelling domestic work. Emerald Paul’s Ariel has a more resigned scorn for Prospero, but you feel her heavy with exhaustion, and a slight hesitance when speaking, because Ariel doesn’t want to face Prospero’s unpredictable wrath, and hopes through appeasement she will win her freedom. Bella-Rose Masty is much more fiery as Caliban, and much more cunning. He shows a bright mischievous spirit when tricking Stephano, played by Andrew Masty, into thinking that if he could kill Prospero, he would become King of the Island. Caliban has learned how to use the European ego against them. Nearly all the white characters are adorned with thick white clown makeup and collars that we would also associate with jesters or circus clowns, suggesting, aptly, that they are all fools. Stephano and Trinculo, played by Lily S, are fools in both the Shakespearean sense and in the colloquial sense here. Andrew Masty does a beautiful job at capturing Stephano’s humorous mix of haughty benevolence with Caliban, showcasing how within racist structures you can have tyrants and more sympathetic rulers, but it makes little difference when the unjust system remains the same. Lily S. complements Andrew Masty’s dimwitted ambition with the drunkard Trinculo, who provides much of the play’s comedy just from the fact that he’s often so drunk he doesn’t even know what in the blazes is going on.

Eva Sack plays Miranda, and I found it interesting that she is the one white character who doesn’t wear white makeup on her face, and I wondered if that was because she had grown up on the island from the time she was three years old. This, of course, doesn’t change her Italian ancestry and heritage, but may change her relationship to the island. Miranda falls in love with Kayli Raye Marr’s soft spoken Ferdinand, achieving her father’s dreams of uniting his house of Milan with Alonso’s house of Naples. As a woman Miranda is simply a rook in her father’s chess game; she is his to indoctrinate as he pleases, and her own personal experiences having grown up isolated on this island will most likely have little sway over her husband’s decisions when he eventually becomes King. The King (Alonso of Naples) is played by Stewart Legere as a mute tragic clown, and one wonders if he is really standing in in this context for James I, for whom Jamestown, of course, was named. James is remembered with an epithet from his own time as “the wisest fool in Christendom.”

One of The Tempest’s most memorable scenes is when Prospero instructs Ariel and, in this case their Spirit Ministers, to conjure a masque to celebrate Miranda and Ferdinand’s betrothal. For centuries theatre directors have created increasingly technologically advanced spectacles for this scene. It proves a challenge in Metu’na’q because Ariel is not a spirit in the sense Shakespeare intended, and so I found the magic at play in this scene, which brings in elements from far into the future, really jarring. I liked the moments when the Spirit Ministers were instead performing traditional Mi’kmaq songs and drumming, because it shows how Prospero, like most Europeans, is happy to enjoy elements from an “exotic” culture, but only when he is the one controlling when and how and why they are being performed.

Prospero is a strange character in Shakespeare’s original text because he is both a villain and, in a way, a hero. In the end he rejects his dark magic, but he never attempts redemption with Caliban, and on the other hand, he leaves victorious over his treacherous brother, off for power and glory awaiting him as the restored Duke of Milan. I was curious whether Stone would somehow change the ending here, but he doesn’t make any changes to the arc of Prospero’s story. The island is left more destroyed for Prospero and Miranda having been there, with Caliban and Ariel’s relationship with one another undercut by over a decade of being pitted against one another. And yet, at the same time, this fictional island is then left alone in a way that Mi’kma’ki, and the Paspahegh’s village at Jamestown that the British settlers brutally sacked and destroyed in 1610, and nearly every single corner of the Earth would never be again. With the benefit of 415 years of hindsight, that does feel like a happy ending.

The Sipu Tricksters production of Metu’na’q (Caliban’s Version), in association with Zuppa, opened August 13th, 2025 and closes tonight, August 17th at 7:30pm. The show is SOLD OUT!

Additional Notes from Zuppa: Trigger Warnings: colonial violence, consumption of alcohol, racism and racial slurs.

Accessibility: this production takes place outdoors, in the evening, which means bugs. Please dress appropriately.

Audience seating is general admission on wooden benches. The show is 1 hour with no intermission.

For assistance, please reach out to info@zuppa.works or call or text 902 489 9872.