Henry Peach Robinson’s Fading Away (1858)

Dr. Roberta Barker is a beloved Theatre Studies professor at the Fountain School of Performing Arts in Halifax and in 2023 she published a book called Symptoms of the Self: Tuberculosis and the Making of the Modern Stage, which was published by University of Iowa Press. It was the recipient of the 2023 Ann Saddlemyer Award, “given to the best book published in English or French in a given year. The winning book should normally constitute a substantial contribution to the field of drama, theatre, and performance studies in what is now known as Canada.”

As soon as Barker told me about the subject of her book I was immediately intrigued and wanted to read it. What could tuberculosis have to do with the theatre beyond being a hazard for folks in the audience during times when the disease was or is considered an epidemic?

After becoming engrossed in the book, I sat down with Dr. Barker to discuss it in more detail, especially because I was so curious how a theatre academic and historian would find tuberculosis as a lens through which to view the Modern Theatre in the first place.

The answer, in short, was that Barker had a deep interest in 19th Century culture dating back to her teenage years. “When I was a teenager I read tons and tons of 19th Century novels… if you do that you get immediately immersed in the world of all the consumptive characters. I was also very interested in poetry and music, so I was kind of growing up on all these mythic historical consumptives: the Brontë sisters, [John] Keats, [Frédéric] Chopin… so that was always sort of an interest to me. Why were these characters and these historical figures so glamorized and kind of iconic?” Barker points out that even Charlotte Brontë, who had seen a number of her siblings die in the horrible reality of the disease, chose to romanticize it in her work. “She makes it this sort of beautiful spiritualizing disease,” Barker says. She also read Susan Sontag’s book Illness as a Metaphor (1978), also as a teenager, and she characterizes it as “[Sontag] was kind of the first person to write about [how] this is a real WTF about 19th Century culture. Why would you have a culture where tons and tons of people are dying epidemically of a really horrible illness that is not beautiful, and yet it is very romanticized in literature and in the culture?”

Barker says that consequently when she was a teenager these sort of “consumptive heroes” were attractive to her. “It was kind of my bag,” she says, and in the Acknowledgments section of her book, she says that many of the folks she names there as having been helpful to her throughout this research process are people who have known her since she was a teenager or in her early 20s. She had also been working on a project where she was looking at “realist acting and realist theatre and how it’s been applied to texts that come before Realism, like Early Modern texts. I was very interested in the vocabulary of Realism,” she says, “and where it came from.” From there she encountered Alexandre Dumas Père’s play Angèle (1833), which, Barker says, “pretty much no one had read, certainly no one who wasn’t a Dumas Père scholar, had read for like 150 years.” Her reaction to the play was that it wasn’t at all what she had been expecting from a play from the 1830s. “There’s a huge period of drama that almost no one is interested in,” she says, referring specifically to this part of the 19th Century canon, especially the plays that were written during this time in France, which she says often is regulated to being a special interest.

“When I read Angèle my mind exploded because I was like this play is full of scenes that could have come out of [Anton] Chekhov. They read like something from the 1890s. It’s massively subtextual and the subtext is all about sex and class struggle and gender power relations, and also about this idea of disease and hereditary disease, and, of course, you have this character who is a doctor who is dying of consumption. I was like ‘what the hell is this?’ And I got so obsessed with this play. I think I can confidently state that I am now one of the world experts on this play… What I got kind of convinced of was that this figure of the consumptive character, which Angèle was one of the plays that pioneered this and was viewed as quite shocking in its time, was a window through which you could actually see the growth of a whole theatrical language of what we now think of as Realism- actually coming out of Romantic, Melodramatic, Sentimental theatre- rather than being a response to it, which I think is the classic theatre history narrative…. Angèle in particular made it really clear to me that, actually, so many aspects of Realism- like depicting everyday contemporary life, interest in heredity, [and] subtext- are all things that actually came out of the sort of Melodramatic and Sentimental tradition, the Romantic tradition, as a way of creating a sort of sense of pathos and a sense of interiority.”

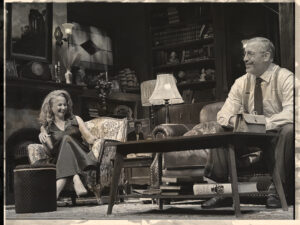

Barker argues that this pathos and interiority were the tools that the Romantics were using to encourage their audiences to feel emotions at the theatre, to cry, and to identify with the characters with empathy. “It’s a legacy that’s still very much with us,” Barker says, connecting this to Neptune Theatre’s recent production of Nick Green’s play Casey and Diana. She says, “From the ‘80s to now this goal of making people think differently about society is very much with us in plays about AIDS, for example.” She notes that even in the 1830s these Sentimental plays were liberal and progressive, in certain ways, and that the “goal involves trying to get audiences to identify with characters and feel for them. How do you do this?” she asks, “You tap into audiences’ everyday experience and things that they find moving. This idea of depicting characters who are suffering from an illness that a lot of people in the audience are either suffering from or know people who are suffering from it, because one in five people, at an estimate, die from [tuberculosis] in this period, so it’s impossible that there’s no one in the audience who has never known anyone who has this illness. I got super interested in tracing how this particular sort of character type of the consumptive goes all through 19th Century and into 20th Century theatre as a way of really depicting interior life, of depicting sort of modernity and, in a way, fusing what we now think of as the goals of the Realist Theatre.”

Barker mentions that Alexander Dumas père and his son Alexandre Dumas fils are remembered today largely for their novels- Dumas Père, of course, wrote The Three Musketeers and The Count of Monte Cristo, and Dumas fils wrote La Dame aux Camélias. Yet, not just their plays, but most others from this period have largely been erased from mainstream theatre history. “I think there’s a huge theatre history problem… the French drama [of this period] was unbelievably influential and very controversial and was being played everywhere in translation throughout the 19th Century, but it’s almost been erased,” she says, noting that the play adapted from La Dame aux Camélias is the exception. “I personally find, especially in textbooks, but even in wonderful pieces of scholarship, that you’ll see the entire early to mid 19th Century theatre being associated with Melodrama and this Dudley Do-Right, Nell on the train tracks, moustache-twirling villains kind of thing. When you read the Dumas, there’s a series of these Dumas Père plays that are set in the contemporary world that are really about very morally complicated characters and situations. Everybody is quite grey. Even the “good” characters do things that [are morally ambiguous/questionable]. What he is very interested in is basically social motivation and the social construction of identity and how people are driven by their backstories and their psychologies and so on. People are not ‘black and white characters.’” Barker says that when playwrights began putting consumptive characters on the stages in Paris in the late 1820s and early 1830s audiences were shocked. “They were like, ‘this is indecorous. This is sort of disgustingly realistic.’ I think if we saw those performances now, if they had been filmed, we would think they were incredibly idealized and non-naturalistic, but for the time, it was this important way in which we sort of put on the table a lot of contemporary questions and ways of thinking and thinking about the body, thinking about the ways that people act are sort of shaped by their bodies and their physical life in the world, and also thinking about things like class, in particular, and gender.”

“Feud says this fascinating thing that [tuberculosis] is the only illness that you can use onstage that people will identify with psychologically,” Barker continues, “He says there’s something about the illness that allows psychological action to happen. I think this is the crux of it, that they understand it as an illness that basically arises out of the psyche and out of emotions. So it becomes a way of externalizing emotions that looks real. Even as the understanding of the science and biology around tuberculosis evolved into the 20th Century consumption continued to retain its more romantic implication onstage.” Barker cites Eugene O’Neill, saying that he had grown up as the son of an actor who had been surrounded by this Sentimental 19th Century Drama, and that he is known in theatre history for being a reactionary against this to become a great American Realist whose work is known for both being gritty and honest. “He literally has tuberculosis and spends time in a sanatorium, and is in the era of Public Health…like this is a bacterial infection… and yet, literally every play in which, and there are more than I even talk about in the book, but there’s three main ones, in which he depicts tubercular characters, including two of them in which he basically depicts himself: totally romanticized and totally connected to emotion. You see that, actually, this sort of mythology is steeped into the way people come to see themselves and their world, even when it’s been kind of debunked by [science].”

Barker says that the other “crazy thing” she encountered when researching this book was that for hundreds of years before the Romantic Theatre illness onstage was almost always funny for the audience. “It was viewed as grotesque… what you would mainly get is satire. So this moment when the ailing body becomes idealized and actually an image of a sort of martyred beauty and glamour and romance and interiority and depth is not a given. It’s an innovation of the Romantic Period. Jure [Gantar] and I had this really interesting moment where our research intersected a number of years ago where he was doing research into comedy in the 17th Century, and in general how comedy works and this idea of making fun of yourself. Making it acceptable. You can make fun of other things if you’re also making fun of yourself, and he used the example of Molière, who we think is someone who suffered from tuberculosis, in that he has a lot of his characters, Le Malade Imaginaire and so on, who are these hypochondriacs or sort of these old guys coughing, and it’s funny. As far as we can tell he lives with [tuberculosis] for quite awhile, which is not an uncommon thing for hundreds of years, and his way of navigating it is, alright we’ll just work it into the character and make it funny. And the audience is good with that.” She goes on to say that Chekhov, “who is literally a consumptive doctor… puts some relatively romanticized consumptive characters on the stage, especially Ivanov, but he, himself, in his own everyday life is downplaying and making jokes about [being sick]. It was fascinating seeing this 360 degrees of a hundred years of a culture where so many people are navigating this illness in their own everyday lives and the lives of their families and their friends, and then are thinking how do you represent this? And these different answers that get put forward: should we make light of it? Should we sort of cleanse it? Should we whitewash it so to speak? That’s another part of the story,” Barker says, which she also writes about in the book, “tuberculosis on stage is extremely connected to whiteness. Which was not at all historically accurate.”

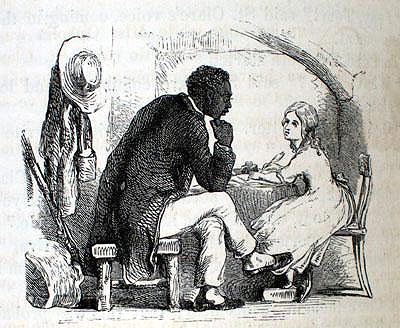

Barker mentions that the medical theory of this time, especially coming out of the United States both before and after the Civil War, was actively, unbelievably, “mind-blowingly” racist, and was being used in the South as a way to excuse and justify, or indeed, affirm the institution of slavery. Tuberculosis was seen as a disease that affected “emotionally complex” white people, and thus, it was believed that Black folks were essentially immune to it. “In Uncle Tom’s Cabin, which is trying to say that [slavery] is cruel and wrong, and we need to abolish this institution, nevertheless, still, [novelist Harriet Beecher Stowe] buys into this idea that it is the little white girl who is the saintly consumptive whose death is going to convert everybody, and Uncle Tom and Tospy, are these kind of hardy, resilient figures- [therefore], even when tuberculosis was sometimes being used to critique certain impacts of racism, it was nevertheless also being used to keep racism quite firmly in place.” It is a strange aspect of white supremacism, Barker remarks, that chastises white folks for being too complex, emotionally deep, and intellectually profound, and thus bringing about this epidemic of illness, and yet, of course, horribly racist to assume those of other races don’t have the needed complexity, depth, and vivid inner life and civility to warrant becoming infected. At the same time, Barker notes, tuberculosis is “literally decimating Indigenous populations. It’s one of the tools of genocide…. But that’s not depicted on stage. [Indigenous characters on stage at this time] always die heroically in battle.” “This story [of consumption] is bound up in all the huge stories of how we end up where we are today in ways that are rooted in 19th Century political culture and social culture, also popular culture and medical culture.”

The consumptive characters, famously, are also written as being heroic in their own right. “Another fascinating aspect of this repertoire is that the most classic thing to say [as a consumptive] is, ‘it’s nothing, I’m fine.’ It’s the heroism of ordinary middle class or working class people, which is not, The Three Musketeers or The Count of Monte Cristo doing these fascinating deeds, it’s literally here is this very ordinary thing that humans have to deal with and I’m dealing with it in a sort of heroic resilient way rather than feeling ostentatious and sorry for myself. I’m here trying to keep my kid alive, if that means I’m going to die, okay, that’s fine, it’s a self-sacrifice… a kind of martyrdom. You’re no longer literally on the cross or being martyred in the arena or going to a crusade, your body is kind of destroying you in response to your self-sacrifice and there is this heroic ethos of ‘greater love hath no person in this than they lay down their life for their friend or their daughter or the person they love.’”

Barker says that because of “abiding sexism and abiding ideas about masculinity in particular” the plays that were written in this period about the “death of a beautiful [consumptive] woman, like Camille and its modern retellings like Moulin Rouge, have survived as cultural touchstones, yet an equal number of plays and novels were written about consumptive men, which have been largely cast to the wayside. “The consumptive hero, I think, was actually chic before the consumptive heroine and it had everything to do with these kinds of debates around masculinity in the period and this bourgeoisification of society, the urbanization of society… the rise of the power of the bourgeois dude who is pretty much spending his life being an accountant or being a doctor or being a lawyer… not these “macho” employments. How do you make that figure heroic?” She describes how Suzanne Voilquin, who had trained as a doctor and was a socialist feminist, who had been abused by her own husband and infected with an STI, and whose mother died of breast cancer after being subjected to misogynistic medical theories by doctors, wrote a review of Angèle in 1833 where she says that the villainous anti-hero in the play is typical of people in power: men who think [because] they’re male they can get away with everything. They don’t have to answer for anything… who is the person who is on the side of the heroine? It’s the bourgeoise working man who is consumptive… she says that he is the icon of what men are going to be like in the future… men who treat women equally, who think that marriage should be founded on love and not power, and why does he get this? Well, it’s partially because his body is weak and so he needs her [in a way that stronger, healthier men do not].”

Barker says she’s now working on a piece that expands on one of the ‘side alleys’ that didn’t make it into her book- looking at the novelist Mary Elizabeth Braddon who is best known for Lady Audley’s Secret. She wrote a number of novels that have these glamorous poetic consumptive heroes in them. “She even makes jokes about it. There’s one of them in which one of the men goes, ‘women have always been suckers for my cough.’ She is quite pointed about the fact that [for] these sort of young, progressive, poetic literary women the idea of these kind of fragile, intellectual, poetic, suffering [men] is very attractive to them.” In her novel Mount Royal a woman is choosing between a consumptive poetic man and a healthier more robust man that she can’t stand, but who her parents want her to marry, and Barker characterizes her feelings saying, “he treats me like an underling, we don’t have an intelligent conversation, he’s got no poetry in his soul,” but the consumptive keeps trying to dissuade her from marrying him because she will have to become his nursemaid, but she would prefer to do that for someone who is kind and smart, while also being able to travel to climates more amenable for tuberculosis patients, than to stay in the city with a man she is sure will be abusive to her. “I think this image of the consumptive male has been kind of edited out because, especially in the late 19th and early 20th Century, there was a real reassertion of the ‘manly man’ [that wanted to] erase the embarrassing Romantic masculinity.” Barker says it drives her crazy when scholarship focuses on a play like Les Dames aux Camèlias and views it simply as “sick voyeuristic masculine fetishization of sickly women” when in fact that “erases decades of female desire that is about female audiences and female readers finding this image of the beautiful young doomed man very attractive for a whole bunch of reasons, one of which is ‘I’d rather be more equal with someone who was more physically fragile and has emotional depth and who kind of gets me… than the macho man who is wanting to kick ass all the time and is just going to treat me like his possession.’”

Barker says that in Illness as Metaphor Susan Sontag critiques the way writers of this period romanticized and glamorized tuberculosis as wrong. She adds, “For me the response to that is: how does a society deal with something this awful that it’s struggling with, something this difficult that has such a deep impact on so many lives? You’ve got to create some narratives that actually at least allow people to work through it… All these stories that they told on stage were a way for them to work through a lot of the questions [they had such as]: why are we chronically ill, what’s wrong with our society?”

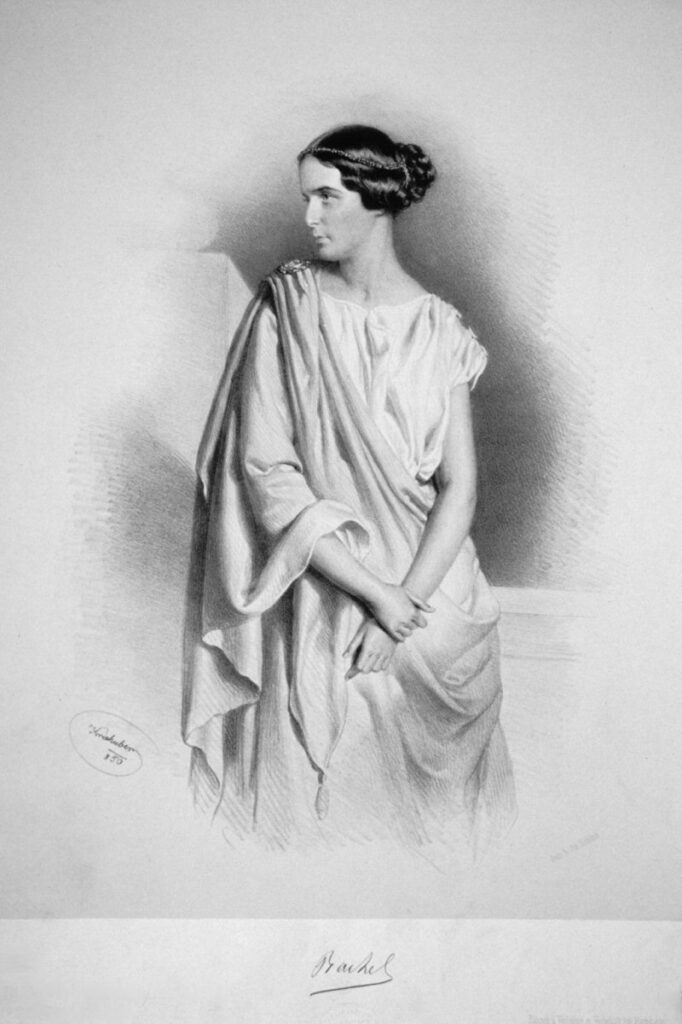

“Another thing that kind of fascinated me is how many people you meet over the course of this story that are not only representing this illness onstage, but who are also living with it.” Barker cites Mademoiselle Rachel, her personal favourite, who was this “tremendous badass.” She came from a Swiss Jewish peddler family, and with her own ingenuity, intellect, and talent she became the most famous classical actress in the world. She also “overtly defies every moral structure of the society.” She made no attempt to hide her love affairs, often with very prominent (and married) men, boasting to folks, “I prefer renters to owners.” She told wild stories about drunkenly performing Phèdre (Jean Racine) on the table for the Czar of Russia. She was always physically fragile and when she becomes sick with tuberculosis she was on tour in the United States and her cast mates were literally having to hold her upright so she could continue to perform despite her illness. “She’s like, ‘I’m gonna effing keep acting. I’m fine.’ And they’re like, ‘You’re Not. You cannot stand.’ And she’s like, ‘I’m good. I’m good!’ She fights and fights and fights.” Barker compares this to the more physically robust Sarah Bernhardt whose sister died from tuberculosis, who advertises herself as “always being on death’s door… and she plays all these famous consumptive characters, but Bernhardt lives until she’s like eighty… She was so tough, but she advertises herself as being thin, and frail and spitting blood, because by then it’s become glamorous and part of her persona. It’s the same thing with Eugene O’Neill… They’re all people who have lived in proximity to this possibility of their own death and who get connected with this web of mythology, but actually their lived experiences of it are quite different.”

“The last great actor that I talked about [in the book] was Charles Ludlum, one of the inventors of kind of out Queer Theatre in New York in the ’70s, whose most famous performance was as Camille in drag with his chest hair sticking out, but in full Greta Garbo 19th Century drag, really having fun with all these tropes.” She tells of the way he would do an over exaggerated coughing fit and then collapse in a heap on his lover’s lap- someone would come in and say ‘oh! excuse me!’ “Only a few years after that Ludlum dies of AIDS and he really lives across the point at which, finally, by the ‘70s, tuberculosis has become a kind of trope, although unfortunately, indeed, infections are [now] rising again, even in the so called ‘West,’… Ludlum was part of that first generation that wasn’t afraid of TB because of effective multi-drug antibiotics, so it could be a joke- and yet this same generation, who, with this kind of joyous Queer aesthetic makes a joke of it, then immediately lives through this horrific epidemic in which so many [Queer folks] are lost, so I think it really speaks to this sense in which the medical and the cultural histories, and we know this from Covid, the artistic and the medical histories of populations are so intertwined in such complicated ways, and the way the narratives that we turn to to try to help us make sense of what happens to us, medically, are really important to think about. … In some ways, if that repertoire in the 19th Century, the Consumptive Repertoire as I call it, had not been there for Ludlum’s generation- would their way of navigating the AIDS crisis and living through it and memorizing the people who didn’t live through it, have been different? I think probably in some ways it would have.”

“It’s easy for us to look back to the 19th Century and be like, ‘isn’t it weird that they dealt with [this disease] in this way, but that was how they dealt with it, and I think in the case of the AIDS crisis we can see the complexity of how a community dealt with- if we look at Angels in America, if we look at Rent, The Normal Heart, the works that came out of the ’80s talking about the AIDS crisis- that language, that came out of the 19th Century theatre, was one of the things that they turned to as a way of making sense of something so horrific and nonsensical, and all these young, beautiful, gifted, cool, smart people suddenly being lost.”

Going back to Angèle Barker says that as Dumas Père encountered tuberculosis more and more in his life he started to put more and more of the reality of it in his work. In this play we see the young characters raging against the illness and how unfair it is to have their futures cut short and limited by an illness beyond their control, not unlike the way Tommy lashes out in anger in Casey and Diana. “When Lockroy who was playing Henri Muller in Angèle did the cough onstage the people were like, ‘I can’t believe he did that’… no matter how romanticized it was… to see it done on stage is shocking and it’s evoking something that is really awful. The more repeatedly represented something becomes, the more it becomes normalized and almost a joke. I think it’s why I’m still really obsessed with [Angèle], that although in certain ways it’s very romanticized, in other ways it’s very honest about this idea of the injustice and stupidity of the whole thing, as in Casey and Diana, becoming connected to the injustice and stupidity of other forms of social discrimination. Why the hell is someone treated as less good because they’re lower class than somebody else? Because they work and the other person doesn’t? Because they’re gay? In what universe does that make any sense? And in what universe does it make sense for somebody young and smart and with all their life ahead of them to suddenly get struck with this illness and to not be able to have their life?”

This is just scratching the surface of all the interesting themes and stories from this time in theatre history- covering French, British, and American experiences- that Barker has both uncovered and chronicled so vividly and with such astute analysis. You can order Symptoms of the Self: Tuberculosis and the Making of the Modern Stage at King’s Co-op Bookstore (6350 Coburg Road, Halifax) or from Chapters.